Synthwave Stadiums and Milk‑Aisle Anomalies

# Synthwave Stadiums and Milk‑Aisle Anomalies

I hit record thinking we would talk about neon and guns, and we did, but the conversation with Malick took a turn I loved. We started with Miami Vice colors splashed across a futuristic stadium, then we wandered into the weeds of UI pain, engine loyalty, and how scope can be the difference between a burnout and a breakthrough. Somewhere between talking about Fortnite’s staying power and a tiger guarding a grocery cooler, I realized this episode was really about permission. Permission to pivot, to time‑box, to make something silly on purpose and see what happens.

## What we talked about

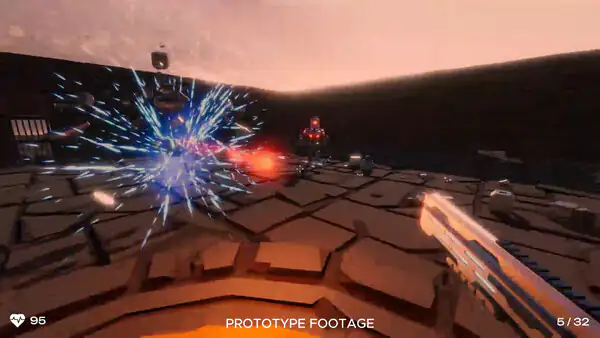

I brought up the vibe first because I could not ignore it. Hundred Caliber Dash looks like a synthwave postcard, and Malick owned that. He wanted color, not another moody sci‑fi corridor. The stadium setting had been stuck in his head for two years, morphing from Olympic hurdles to a PC shooter. He prototyped in Unity, Unreal, and Godot before going back to what he knew best: Unity’s ecosystem, tutorials, and asset store. Godot tempted him with a cleaner UI system and themes you can define once and reuse everywhere, but the support gravity pulled him home.

We both commiserated over UI. I told him how I turned Unity into a dollar‑store Canva just to keep my menus sane. He laughed because Godot basically gives you that flow out of the box. Then we got into weapons and loop design. Hundred Caliber Dash runs on a simple, readable idea: two pistols that act like different classes. Left click is your reliable pistol, right click fires your heavier, close‑range punch. Each has its own ammo, and perks knit them together at the end of each run. The timer is your health, so speed equals survival. Kill to get time back. It is post‑void energy with a track‑meet name, and the stadium theme ties the whole thing together.

Fourth, the marketing mind split is real. Building and promoting at the same time strains your attention, which is why the one‑month product rule felt smart. He developed, then promoted. That single change made the work feel lighter, and the traction proved it. Influencers who ignored the stadium shooter answered DMs for the milk run. Sometimes the joke is the bridge. It is not selling out. It is understanding that distribution is a design problem too.

Finally, community‑driven iteration is a superpower when the systems are simple. Malick architected anomalies so adding a new one took minutes. Streaming then became a co‑design session. Viewers asked if the TV turns on. Five minutes later, it did. That is the kind of loop you want between audience and feature set. It is not just engagement; it is actionable scope discovery.

## My closing thoughts

I love the ambition of Hundred Caliber Dash. I also love the audacity of Daddy’s Long Milk Run. Together they tell a story I want more indie devs to hear. You are allowed to time‑box. You are allowed to chase a meme if it buys you reach. You are allowed to pick the tool that makes your life easier even if it is not the cool one this week. Most of all, you are allowed to design for joy, not just for a checklist of best practices.

There is a season for neon pistols in a roaring stadium, and there is a season for a supermarket where reality blinks and a tiger explains why someone never came home with milk. If one carries the other across the finish line, that is not luck. That is craft plus timing, which is the closest thing we get to a plan in this business. Next, I want to see Dash keep leaning into its bright, readable speed and perks that reward rhythm. I want Milk Run to keep feeding the anomaly machine with community ideas. And I want both projects to remind me that playfulness is not a distraction from the work. Sometimes it is the shortest path to the win.

Episode Info

From there we talked marketing pressure. Demos, wishlists, influencer spreadsheets. Malick did that dance for Dash, got good feedback, and shipped a tighter demo after fixing clarity issues like reload communication. Then he admitted he was tired. So he took a breath and did something I respect a lot: he scoped a new project to a month, start to finish, and made it silly on purpose. Daddy’s Long Milk Run is an anomaly spotter in a supermarket, riffing on that meme about dads going to get milk and never coming back. He built it in two weeks, spent the next two promoting, streamed the process, and let chat suggest anomalies in real time. The cat NPC? A hit. The tiger? Confusing at first, then a signature bit. And of course the internet loves both.

## What stood out / lessons learned

The first thing that stuck with me was how constraints unlocked momentum. Malick’s stadium fixation could have been a trap, but it became the thread that aligned genre, aesthetics, and naming. Once he said it out loud, everything else snapped into place. That is a real indie pattern. Pick a constraint that excites you, and let it narrow your choices. It is easier to make bold decisions when the box is smaller.

Second, engine choice is rarely about purity. It is logistics. He preferred Godot’s UX, but Unity’s asset depth, docs, and his own experience meant fewer unknowns in a solo sprint. That does not make one engine better; it makes the decision honest. If you are shipping, not scoring points in a forum argument, familiarity is a feature.

Third, clarity always beats clever in first person design. Players told him a dimmer glow on the gun was not enough to communicate reload. He added proper feedback, the demo felt better, problem solved. We forget how much invisible UI work props up a clean loop. If a player does not know why they cannot shoot, the loop is broken no matter how stylish the neon is.