The Coffee-Cup Rule and the Mountain We Chose to Climb

# The Coffee-Cup Rule and the Mountain We Chose to Climb

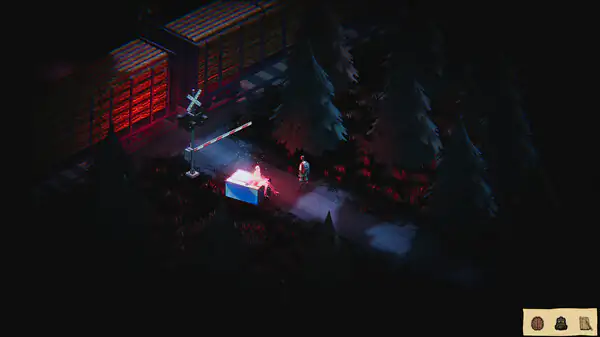

I knew I was in for a good hour the moment Arttu dropped the line about designing a game you can play with a coffee cup in one hand. That visual stuck with me. Feet up, one hand free, story doing the heavy lifting. It sounded cozy. Then he and Oskar started describing Paradigm Island and I realized cozy isn’t the whole story. It’s dialogue-driven, a little dark in the corners, quiet in the best way, and built by a small team learning as they go while trying to ship something honest. My kind of chaos.

## What we talked about

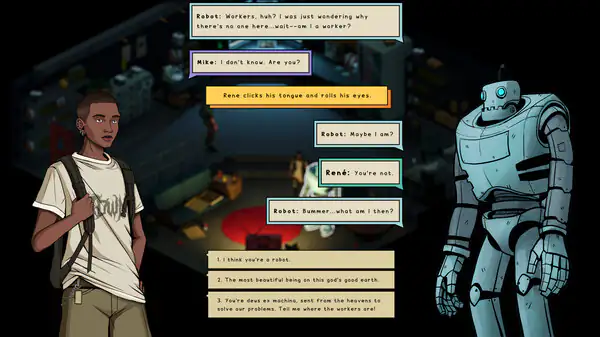

Paradigm Island started life as a webcomic. That origin explains a lot about its look and pacing. You can feel the panels in the way they talk about scenes, the way choices branch, the way mood acts like another character. When Arttu bumped into Oskar and pitched it as a game, they had the right mix of skills to give it a shot. He writes, models, and wrangles sound. Oskar is the technical lead, living in C# and Unity. They founded End All Entertainment and dove headfirst into production.

They learned quickly that “fewer mechanics” doesn’t mean “less work.” It means writing every second of experience. If you aren’t leaning on combat systems or elaborate traversal, you’re crafting the moment-to-moment by hand. That’s the beautiful trap of narrative games. The demo is already on Steam, the median session is around thirty minutes, and while downloads are still modest, the people who do play tend to stick. That’s a strong signal, especially for a dialogue-first project.

We covered language choices too. With roughly two hundred thousand words on their plate, translation isn’t realistic at launch for a five-ish person team. English first, maybe more later if sales allow. We spent time on team dynamics, the fluid headcount that comes with bootstrapping, and the not-so-glamorous business tasks that ride shotgun with creative work. They’re part of a university incubator, which means they’ve got real desks, real routines, and that underrated mental shift you get from commuting to a space where the work lives.

Fourth, scope is elastic right until you force it to behave. They admitted the game got bigger, then smaller, then sharper. That’s not failure. That’s design. When your core is conversation and choice, every extra branch multiplies cost. Trimming is craft. Their confidence now comes from known burn rates: this much content takes this much time. That’s how you protect the ending from fantasy deadlines.

Finally, the long game. I loved how casually they framed success. Shipping is the win. Revenue is oxygen, obviously, but credibility compounds. One shipped game turns a pitch into a meeting. Two shipped games turn a meeting into terms. They plan to reuse tech and pipelines, keep living in the narrative space, and get very, very good at one genre. That’s not narrow. That’s focus. The second project is where the leverage shows up: fewer unknowns, better estimates, higher ceiling.

## My closing thoughts

Paradigm Island looks like a cup-of-coffee experience until you hear the edges in their voices. It’s thoughtful and a bit dangerous, like a story told in a low room with a heavy lamp. It’s also a case study in building the studio while building the game. There’s a version of this journey where the team chases novelty, swaps engines, pivots to whatever’s trending, and never ships. That’s not the path here. They chose the simple stack, embraced constraints, and let the writing carry the weight.

If you’re an indie dev or an entrepreneur lurking at the overlap, this episode is a friendly nudge. Write your why. Protect your scope. Test earlier than feels comfortable. Don’t be precious about the medium if the idea wants a different home. And whatever you do, design for a real human on the other side of your choices. Preferably someone with a coffee in hand, one thumb free, curious enough to see what happens if they ask one more question.

Paradigm Island lands on Steam soon with a demo you can play today. I’m rooting for the spike that every small studio dreams about, but I’m even more excited for the second mountain they’ll climb after this one. That’s where the view usually gets interesting.

Episode Info

On tools, they chose Unity because it was familiar, not because of anything romantic. Both had cracked it open in school, and the tutorial ecosystem is deep. C# felt approachable. The first six months were mostly learning the engine and building muscle memory. Since then it’s been iteration on everything, especially readability. Isometric scenes are beautiful until the pathing confuses players. Their oil rig level? Rebuilt. The dialogue UI? Same layout since day one, but if you compare last year’s build to today’s, it’s night and day.

Marketing came up in the most indie way possible. They’re ramping late, running ads, planning Next Fest close to launch, and embracing the spray-and-pray reality of content. You can’t predict what resonates. You just show up often enough to be present when something does. If a mid-tier streamer falls in love with a cozy-looking game that turns out to have teeth, that’s a great day. Until then, ship the vertical slice, test relentlessly, and make the next minute of the game.

## What stood out and what I learned

First, the webcomic DNA matters. It reminded me that distribution can follow the idea. Start where your skills are sharpest, then move the story to a format that fits the market you want. That’s not selling out. That’s being strategic. They didn’t abandon the point of view; they chose a medium where that point of view could sustain a studio.

Second, documentation is culture. Oskar talked about the growing pains of bringing people in and realizing the “big picture” lived in their heads. The fix wasn’t more meetings. It was writing things down. The moment you write the game’s why, the art rules, the narrative boundaries, and the UX pillars, the project stops being fragile. New teammates either buy in or opt out, and both outcomes save time. I’ve seen this in business for years, but hearing it from a young studio hits different. In games, a well-kept bible isn’t bureaucracy. It’s velocity.

Third, testing earlier than your ego wants is the cheat code. Valve’s philosophy came up: build a little, test a lot. It’s brutal to show work that isn’t polished, especially in a medium where presentation is half the spell. But the alternative is worse. If you test late, you learn late. If you learn late, you ship a museum piece. Their approach with multiple demos made sense to me: some are rough to probe mechanics or narrative pacing; the public Steam demo is a marketing slice built to win wishlists. Same idea, different intent.