The Pawn That Learned to Jump

# The pawn that learned to jump

I love when an idea sounds ridiculous at first and then, five minutes later, it starts to feel inevitable. That was my vibe talking with Doug about his game, Who Wears the Crown. Picture a pawn, not politely shuffling one square at a time, but bouncing through a gauntlet of chess puzzles while pieces slide into place with that satisfying Plinko clatter. It’s part precision platformer, part real chess, and somehow it works. The funny part is Doug didn’t build it because he worships the genre. He built it because he wanted to be intentional about making something people would actually notice and buy. Turns out practicality and creativity can be friends.

## What we talked about

We started with release week. Doug expected the big sales spike on day one. Instead, release day was steady and the real lift came the following weekend and into the next week. The algorithm giveth, the calendar taketh, and apparently Tuesday launches are great for sliding into weekend visibility.

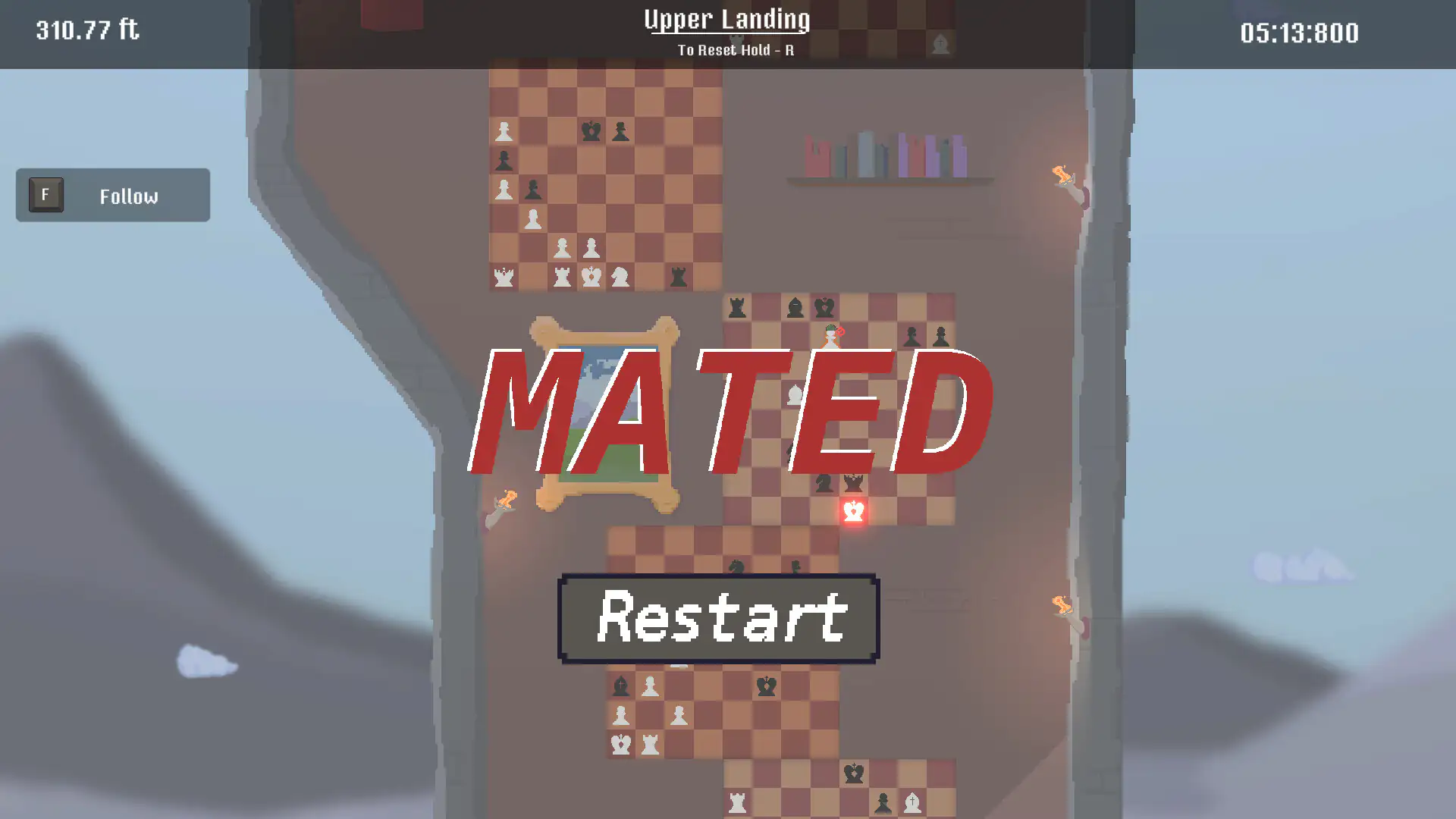

From there we got into the design. The game runs on the Stockfish chess engine under the hood, so the boards are real positions with real responses. Early on, Doug leaned heavy on platforming with a timing‑sensitive jump that could send you tumbling. After feedback, he shifted the focus toward chess. Now you solve bite‑sized puzzles, hit a forced checkmate, earn a super jump, and climb to the next section. If you’re checkmated you drop back, learn, and try again. It’s simple on paper, tricky in practice, and very watchable.

He also fought one of those hilarious technical constraints that only appear once you ship: you can only spin up one instance of Stockfish at a time. When you’re juggling over a hundred boards, that means all kinds of edge cases as players mash pause, restart, and click between puzzles. It’s the kind of bug parade you don’t get in prototypes because no one plays like real players until it’s out in the wild.

We dug into difficulty and audience too. The Venn diagram of people who love chess and people who love precision platformers is not exactly a full overlap. Some players hated missing jumps, others didn’t want to think three moves ahead. Doug’s answer was custom settings. You can lower or raise the engine strength to reduce randomness, turn off jump failure if you just want the chess, or lean into the platforming if that’s your lane.

Fifth, settings as strategy. Customization isn’t just accessibility; it’s audience expansion. Tuning the engine rating higher actually made behavior more consistent and the puzzles more readable, which reduced frustration. Toggling jump failure helped chess‑first players stick around long enough to become platformer‑curious. That’s product‑market fit thinking disguised as a menu.

Finally, sanity. Doug took a two‑month break mid‑development and came back with a clearer eye, pivoting the emphasis from jump timing to chess puzzles. Breaks feel like heresy when you’re deep in a build, but it’s often when the real direction shows up. I’m taking that to heart as we sprint toward October. A short reset now can save six months of stubborn later.

We also touched on AI. Doug’s take mirrored what I’ve seen shipping products: these tools can accelerate scaffolding, but they still need a vigilant editor. They are not a replacement for taste, domain knowledge, or architecture. Use them to explore, not as a crutch for understanding. When the work gets real, you want to know why the code behaves, not just that it compiles.

## My closing thoughts

I came away energized. Doug didn’t wait for permission, he designed backward from attention, and he listened closely once real players showed up. That’s the indie loop in a nutshell. Start with a hook that earns its seconds. Ship a demo that invites people in. Treat feedback like data, not doctrine. Add the quality‑of‑life touches that make your core clearer. Then keep going.

For Troublemakers, I’m doubling down on those lessons. Make the pitch obvious. Show the fun early. Let October be noisy on purpose and measure what actually lands, not what I hoped would land. And when the inevitable bug parade marches through, remember that the parade is proof people care enough to stomp around in your world.

Games are this messy handshake between art, engineering, and community. If you do it right, a pawn learns to jump, a Tuesday launch finds its weekend, and a tiny Discord feels like a studio. That’s the magic. I’m glad we captured a little of it in this conversation.

Episode Info

On the business side, Doug marketed for only a handful of months but still stacked a healthy wishlist count by leaning into the high‑concept hook. In short videos the pawn falls, the pieces clack, the board comes alive, and viewers stick around long enough to get it. He put the Discord link in the demo, invited feedback, and the community delivered. They even nudged him toward quality‑of‑life wins like animating piece movement so spectators can track what just happened. Speedrunners, of course, showed up immediately and started breaking things in the most helpful possible way.

We compared notes on my own project, Troublemakers. We’re targeting a Halloween early access because the vibe fits, and October is our self‑declared judgment month. That means key art refreshes, scrappy ad testing, festivals, and a big push on wishlists. Multiplayer adds its own chaos, but keeping it casual has been our north star to avoid the sweaty meta that chokes the fun out of new players.

## What stood out and what I learned

First, the timing myth. Day one isn’t everything. For a small team, the real curve can happen once the platform has a chance to surface you and folks finally have free time to try what they saved. That’s a helpful note for anyone planning a launch calendar. Pair your date with how the store promotes into the weekend, not just the drama of a countdown.

Second, the value of a crisp concept. If you can describe your game in one clean sentence and instantly picture the moment‑to‑moment, your marketing gets a head start. Who Wears the Crown communicates itself in two seconds. That earns time for the deeper pitch about difficulty, discovery, and humor. As builders, we talk about finding a wedge. This is what it looks like in practice.

Third, feedback triage is a real skill. There are professional complainers on the internet and they are very productive. The trick is spotting the comments that reveal a usability gap versus the ones that just want to watch the world burn. Doug’s tweak to animate piece moves was tiny, but it multiplied clarity for both players and viewers. Small clarity wins compound. They also make your trailer and shorts better because people don’t get lost.

Fourth, tool constraints shape design. A single Stockfish instance forced Doug to rethink flow, state, and edge cases. Constraints like that sound annoying, but they quietly enforce better architecture and player experience. I love this part of indie work. You can’t brute force scale, so you get clever.